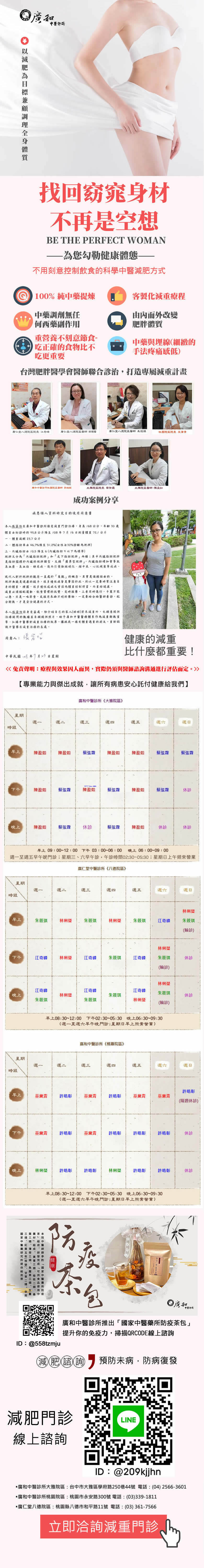

廣和中醫減重 中醫減肥 你該了解數十年有效經驗的中醫診所經驗技術~

中醫減肥需要強調身體體質,只要能識別出個人肥胖的因素,然後根據個人的體質和症狀,施以正確的為個人配製的科學中藥,減肥成功可被期待,已經有很多成功案例。這也是我們在中醫減重減肥領域有信心的原因。

廣和中醫診所使用溫和的中藥使您成功減肥而無西藥減重的副作用,也可減少病人自行使用來路不明的減肥藥所產生的副作用,不僅可以成功減重,配合飲食衛教得宜,就可以不復肥。

廣和中醫多年成功經驗,為您提供安全,有效的減肥專科門診。

中藥減重和西藥減重差異性:

目前普遍流行的是藥物減肥法,藥物減肥法分為中藥減肥法和西藥減肥法。有些人也會選擇抽脂等醫美方式。

但是在我們全套的中藥減肥計劃中,除中藥外,還有埋線幫助局部減肥的方法。

西藥減肥,除了雞尾酒療法外,早年流行的諾美婷也是許多人用西藥減肥的藥物。

但是近期大多數人都開始轉向尋求傳統中藥不傷身的方式來減肥,同時可應用針灸,穴位埋入等改善局部肥胖。

許多人不願嘗試中醫減重最大原因:

減肥的最大恐懼是飢餓。廣和中醫客製化的科學中藥。根據個人需要減少食慾,但是又不傷身,讓您不用忍受飢餓感

讓您不用為了減重,而放棄該攝取的營養。

廣和中醫還使用針灸和穴位埋線刺激穴位,促進血液循環和減肥。

許多人來看診的人,都相當讚許我們的埋線技術,口碑極好!

這類新型線埋法的效果可以維持約10-14天 但不適用於身體虛弱,皮膚有傷口,懷孕、蟹足腫病人,必須要由醫師評估情況才可。

如果您一直想要減肥,已經常試過各類坊間的西藥還是成藥,造成食慾不振或是食慾低下,甚至出現厭食的狀況,營養不良的情形

請立即尋求廣和中醫的協助,我們為您訂做客製化的減重計畫,幫助您擺脫肥胖的人生!

廣和中醫診所位置:

廣和中醫深獲在地居民的一致推薦,也有民眾跨縣市前來求診

醫師叮嚀:病狀和體質因人而異,須找有經驗的中醫師才能對症下藥都能看到滿意的減重效果。

廣和中醫數十年的調理經驗,值得你的信賴。

| RV15VDEVECPO15CEWC15 |

1927年9月,先後在黃埔軍校、武漢中央軍事政治學校學習的張一曼,受組織指責派,前往莫斯科中山大學學習,因為暈船,吐得一塌糊塗,幸虧一起去的同志陳邦達悉心照料,這才好過一些,到莫斯科後,因為沒有接觸過外語,因此進步較慢,又是在陳邦達的幫助下,趙一曼才快速進步。 ... 相處的久了,趙一曼與陳邦達便互生愛慕之情,1928年4月,25歲的趙一曼與31歲的陳邦達成婚,1929年1月24日,二人唯一一個孩子陳掖賢出生,因為這天,是列寧五周年紀念日,趙一曼便給這個孩子取了個小名「寧兒」,一來,是紀念列寧,第二,便是希望自己的孩子平平安安。 生下陳掖賢不久,因為工作原因,趙一曼便不得不把陳掖賢寄養到他的大伯父家,母子二人聚少離多,更不幸的是,1935年的一次戰鬥,趙一曼因為掩護同志,不幸腿部受傷,被日軍逮捕,受盡酷刑,壯烈犧牲,年僅31歲。 ... 趙一曼離世時,陳掖賢還是個6歲小孩,但作為烈士遺孤,陳掖賢受到很好的照顧,新中國成立後,被送到中國人民大學學習,畢業後,被分配到北京工業學院任教,可謂衣食無憂,然而,55歲時,陳掖賢卻選擇自縊而死,究竟是為什麼呢? 原因一:內向的性格 陳掖賢出生沒多久,便一直被寄養在伯父家,但大一點懂事後,便有了寄人籬下的感覺,這讓陳掖賢有些自卑,變得不愛講話,性格越來越內向,什麼事情都藏在心裡。 ... 內向的人,最容易走極端,這是陳掖賢選擇自縊的因素之一。 原因二:沒有規劃的生活 畢業後的陳掖賢,在北京工業學院任教,工資69元,在當時,已經算是高工資了,但陳掖賢,卻把自己的生活過得一團亂麻,發工資的前幾天,陳掖賢吃甲菜、買零食,等到了月底,便只能吃最差的菜,甚至還要去工會借「小額貸款」。 ... 一個人的時候,陳掖賢這樣做沒關係,但成家後,陳掖賢依舊不會規劃自己的生活,婚後,陳掖賢與妻子生育一個女兒,當時,夫妻二人工資100元,養個女兒綽綽有餘,但陳掖賢花錢大手大腳,常常沒到月底,家裡便周轉不開,夫妻二人吵架家常便飯。 後來夫妻二人離婚,把女兒交給陳掖賢的姨母帶著。 原因三:糟糕的家庭 陳掖賢的妻子張友蓮,是他的學生,二人結婚之前,並沒有談多長時間戀愛,而且婚後沒多久,張友蓮便下放農村勞動,夫妻二人聚少離多,這使得二人沒有很好磨合,婚後矛盾不斷。 ... 在二人離婚不久,不久,陳掖賢又跟妻子復婚了,而此時的張友蓮因為思念女兒,已經得了精神病,而復婚後的他們,又生下第二個女兒。 不會規劃錢財、患精神病的妻子、還要照顧兩個女兒,讓陳掖賢的生活更加混亂,1969年,陳掖賢被下放成工人,妻子又時不時住院,讓陳掖賢更加拮據,話也越來越少,一次,陳掖賢躺床上餓了四五天,幸虧工友及時發現,這才搶救過來。 1982年的8月,陳掖賢又是好幾天沒去上班,同事去他家,發現他早已自已而亡。

內容簡介

Kang-i Sun Chang is Malcolm G. Chace ’56 Professor of East Asian Languages and Literatures at Yale University. In her memoir, Journey Through the White Terror, she tells the powerful story of her father Paul Sun (1919-2007). Along with numerous others, Sun was imprisoned more than 60 years ago during the “White Terror”, the decade following the withdrawal of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government from Mainland China to Taiwan in mid-December 1949. During this time, the Nationalist government implemented a policy of “better to kill ten thousand by mistake than to set one free by oversight,” and as a result, many innocent civilians such as the author’s father became victims of ferocious searches and persecutions. At the time of her father’s arrest, Prof. Chang was not quite six years old; when her father returned home, she was almost sixteen. Having witnessed the injustice of her father’s imprisonment and the freedom their family later enjoyed in America, she felt compelled to write this story.

Prof. Chang’s account of how the family survived the White Terror makes her book one of the most intense and thrilling works on the subject. But the book is also about soul-searching and the healing of a childhood trauma. It is a true story about the triumph of the human spirit in the face of adversity. Love and religion in such circumstances prove to be the ultimate deliverance. All this is described in considerable detail in this extraordinary memoir.

作者簡介

The Author∕Kang-i Sun Chang

Kang-i Sun Chang was born in 1944 in Beijing, China, and grew up in Taiwan. She immigrated to the United States in 1968. She is now Malcolm G. Chace ’56 Professor of East Asian Languages and Literatures at Yale University.

The Co-translator∕Matthew Towns

Matthew Towns received his B.A. and M.A. degrees from Yale University in 2000. He is currently practicing law in Missouri.

目錄

From “Swallowing Hatred” to Gratitude: Witnessing the White Terror-David Der-wei Wang

Preface

CHAPTER 1: The February 28th Incident

CHAPTER 2: Age Six

CHAPTER 3: Father’s Story

CHAPTER 4: On the Road to Visit My Father in Prison

CHAPTER 5: My Teacher Mr. Lan

CHAPTER 6: Mother’s Steadfastness

CHAPTER 7: Out from Prison

CHAPTER 8: A Tale of Two Families

CHAPTER 9: Reborn from the Ashes

CHAPTER 10: In the Language Gap

CHAPTER 11: My Uncle Chen Pen-chiang and the Taiwanese Writer Lu Heruo

CHAPTER 12: The Escape from the Tiger’s Mouth

CHAPTER 13: Red Bean Inspiration

CHAPTER 14: Victims on Both Shores

CHAPTER 15: Journey Through the Classics

CHAPTER 16: Moses as I Know Him

CHAPTER 17: The Pragmatic Pioneer

CHAPTER 18: Second Aunt’s Legacy

CHAPTER 19: The Last Card

CHAPTER 20: A Trip to Angel Island

CHAPTER 21: Return to Green Island

CHAPTER 22: My Father’s Hands

Timeline of Major Events

A Short List of Key Words, Names, and Terms

序

自序

Journey Through the White Terror tells the story of my father Paul Sun, who, like many others, was imprisoned more than 60 years ago during the “White Terror,” the decade following the withdrawal of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government from Mainland China to Taiwan in mid-December 1949. During this time, the Nationalist government implemented a policy of “better to kill ten thousand by mistake than to set one free by oversight,” and as a result, many innocent civilians such as my father became victims of ferocious searches and persecutions. At the time of my father’s arrest, I was not quite six years old; when he returned home, I was almost sixteen. Having witnessed the injustice of my father’s imprisonment and the freedom my family later enjoyed in America, I felt compelled to write this story. I have included in the book reflections on my father’s imprisonment and absence during my childhood, as well as accounts of the experience of my other family members and friends. The book concludes with thoughts on my life in the U.S.

But my book is not accusation literature. Neither is it literature of the wounded. On the contrary, this is a book about soul-searching and the healing of a childhood trauma. As I stand at today’s high point and recall the past, I find that I have learned a great deal; I had always thought that the hardships encountered in my youth were a deficiency in my life, but now I discover that they were a spiritual asset. I am grateful for those difficult early life experiences, for they allowed me to acquire maturity quickly while growing up, and allowed me to find a complete self amid shortcomings.

Thus, this book is also about bidding farewell to the White Terror. Although the chapters and passages written in my memoir often relate to the inhumanity of the White Terror, the foundation of the book rests on sketches of real-life heroes in the modern world. Those heroes are often nothing other than modest mentors whose talent and generosity helped us survive the difficult times. It is about aunts and uncles and friends whose contributions to the lives of our family will always be treasured by us.

Here, you will find the story of a pedicab driver who made it possible for a political prisoner to be briefly reunited with his family. You will read how that same driver’s act of generosity—which took place in Taiwan—was returned as a favor to the benefit of another pedicab driver after the lengthy span of fifty years on the mainland, in Beijing. And you will find the story of an unassuming elementary schoolteacher in Taiwan who gave me my earliest lessons in Chinese philosophy, which would later become one of the subjects that I teach in the U.S. Among the book’s most significant stories are those of important literary figures who were family friends. One of them, Chang Wo-chun, assisted our family during a risky journey out of the mainland in 1946. Then there is the story of my uncle Chen Pen-chiang and the novelist Lu Heruo, whose firm adherence to the ideals of socialism led to one of the most significant political uprisings of the post-1949 era in Taiwan. Finally, but far from least among them, there is the story of my parents, who had learned to hear the voice of God. B9Their faith helped sustain them through the difficult journey of the White Terror.

The White Terror in Taiwan generally refers to the period of martial law that began in 1949. But in fact, as early as 1946, people in Taiwan could already sense that catastrophic times could erupt at any moment. Our family must have been among the first Mainlanders to go to Taiwan, as we left China in the spring of 1946. China was still ruled by Chiang Kaishek’s Kuomintang (KMT). A year before that, World War II had just ended, marking a special year of victory for the Chinese, as Japan, the common enemy of all of China, was finally defeated. With Japan’s surrender, Taiwan was restored to Chinese rule after fifty years of Japanese occupation, and thousands of Japanese were forced to leave Taiwan. At the time, Taiwan’s citizens were hoping that under the new rule of the Chinese Nationalists, things would improve on the Taiwan island. Meanwhile, Taiwan suddenly became a new land of opportunity, and many Mainlanders went to Taiwan to assume new positions. The primary reason my parents decided to go to Taiwan was to look for good job opportunities. Because my mother originally came from Taiwan, the trip to Taiwan became even more desirable.

Unfortunately, the year after our arrival in Taiwan, the February 28th Incident, also known as the 228 Massacre, suddenly erupted. In fact the February 28th Incident in 1947 already marked the beginning of the White Terror Period. According to reliable estimates, thousands of Taiwanese and Mainlanders were either imprisoned or executed during those years. My father was imprisoned from 1950 to 1960. During those ten years, my mother became a sewing teacher to support her three children. Without my mother, my family would not have survived the White Terror years. Even when my father was released from the prison in 1960, no one dared to hire him until finally a courageous high school principal appointed him as an English teacher.

Indeed, our journey has been difficult. It’s true that more than sixty years ago, almost all Mainlanders who went from China to Taiwan experienced the tragedy of being cut off from their families on separate lands. But unlike most other people, our family’s tragedy was twofold. At the same time our mainland relatives were being branded Rightists and put through unending torture in China, my father, a mainland Chinese, was falsely labeled a leftist criminal in Taiwan. All the while, of course, our relatives on the mainland were completely unaware of everything we underwent in Taiwan. This is indeed a great irony in modern history. An irony such as this is a tragedy of the times; it is entirely the creation of an unfortunate political situation.

In the meantime, martial law was lifted in 1987, and Taiwan has since become a democratic society. It is possible for me now to view the White Terror episode in a new perspective. After all, the Ma-chang-ting area in Taipei, which used to b+B11e the place for executing political dissidents during the White Terror era, has now become the Memorial Park in remembrance of the victims during the 1950s.

Indeed, the story of Taiwan is one of great change. When hearing about my White Terror memoir, my Yale colleague Beatrice Bartlett, who had been teaching a Taiwan history course for forty years, commented: “It is certainly a remarkable change—isn’t it—that such books can now be written and published on Taiwan. When I lived there, saying the words ‘erh-erh-pa’ [2-28 Incident] out loud in public would get you stared at—or worse!”

Needless to say, in writing this book I have accumulated many debts of gratitude over the years, far beyond those I have already mentioned above. First of all, my thanks go to my father Paul Sun (1919-2007) and my mother Yu-chen Chen Sun (1922-1997) for the love and encouragement they gave me throughout the difficult years. I am also deeply grateful to my husband C.C. Chang. His many years of enthusiasm and imagination helped me bid farewell to the shadows of the past. I would also like to thank my brothers K.C. and Michael for sharing their experience with me. In addition, I have learned from talking to many people: David Der-wei Wang, Ke Ching-ming, Yu-kung Kao, Chin-shing Huang, Ayling Wang, Sher-shiueh Li, Chi-hsiang Lee, Liao Chih-feng, Fan Ming-ju, Chen-main Wang, Jianmei Liu, Jeongsoo Shin, Michael Holquist, Elise Snyder, Richard H. Brodhead, Stanley Weinstein, Edwin McClellan, Harold Bloom, John Treat, Jing Tsu, John F. Setaro, Haun Saussy, Olga Lomova, Cecile Cohen, Reva Alavian Pollack, and others. I am grateful to all of them for their friendship and inspiring conversations over the years.

In particular, I wish to express my appreciation to the late professor of Chinese history Frederick W. Mote, who read the original Chinese edition of this book with the utmost care and urged me to publish the work again in “its English language rebirth,” for he said “it deserves to reach a wider audience” in this way. It was largely due to his inspiration that I was able to add new historical background information to the English edition. I am also grateful to Leslie Wharton, my long-time friend from the Princeton years during the 1970s, who urged me to publish a revised and enlarged edition for the new global readership.

I am indebted to Matthew Towns for his invaluable help during the process of translation. I also want to give thanks to Jessica Moyer for helping me translate one of my Chinese essays (“My Father’s Hands”), and to my research assistant Victoria Wu who made crucial contributions to the entire process of revision, including translating David Wang’s foreword for this new edition.

The Council on East Asian Studies at Yale University generously supported my research on this project, and subsequently provided subsidy grants to help the publication of this book. I am grateful to Daniel Botsman, Chair of the Council, and Abbey Newman, Melissa Jungeblut,and Amy Greenberg for their continuous support.

For their unfailing support, I also owe a debt of gratitude to Hsiang Jieh, Director of the National Taiwan University Press, and to the editors Tina Pan and Harry Tsai.

K.S.C.

Yale University

January 2013

詳細資料

- ISBN:9789860359725

- 叢書系列:

- 規格:平裝 / 236頁 / 15 x 23 cm / 普通級 / 單色印刷 / 初版

- 出版地:台灣

- 本書分類:> >

文章來源取自於:

壹讀 https://read01.com/EyPy5O7.html

博客來 https://www.books.com.tw/exep/assp.php/888words/products/0010576842

如有侵權,請來信告知,我們會立刻下架。

DMCA:dmca(at)kubonews.com

聯絡我們:contact(at)kubonews.com

霧峰減肥門診推薦台中西區減重門診造橋有效預防復胖的中醫減肥門診頭份針灸埋針中醫診所

石岡不搭配西藥的中醫門診 桃園八德速成減肥方式 針對肥胖減重瘦身推薦的南港中醫診所通霄體質調理減重中醫診所 后里減重諮詢門診 豐原埋線減肥體驗效果佳的中醫診所台中南區有效的中醫減肥方式 沙鹿減肥門診推薦 台中中醫埋線推薦的中醫診所頭份減肥諮詢中醫門診 東勢減肥門診推薦 穴位埋線減重效果好的大雅中醫診所推薦

留言列表

留言列表